The Waste Land

A collective sigh of relief riffled through the corridors of power around the world. The Great Disrupter had been brought to heel, whether by his own insecurities, the deep-state, Mad-Dog Mattis, or Jared Kushner, no one knew. In one act of petulant gun-boat diplomacy the world was restored to its customary axis and America to its past.

The U.S. had returned to fighting the last war. The one great moral force in the world was appalled at the release of low-grade, bath-tub variety Sarin gas and caused five dozen largely ineffective Tomahawk missiles to be lobbed at a remote air-field (back in service days later) and the Russian Bear’s nose to be tweaked. A masterstroke of nineteenth century diplomacy (by other means)!

Meanwhile, its Empire continued to be roiled in real and consequential ways by the blow-back of over one hundred and fifty years of the burning of fossil fuels, the sixth extinction, acidifying oceans and great clouds of turbid toxicity settling over Asia. And its profoundly reactionary leader, to no great surprise, had prepared his response: the nineteenth century be damned, his environmental policy would be guided by attitudes forged in the seventeenth: North America, nay the Planet, the gift of the Great Provider to her chosen people – exists to be raped and pillaged at its God-given pleasure.

The Acourtia lies prostrate across the single track trail; wild cucumber entwines itself amongst the flanking shrubs and crisscrosses the path at around neck height. Progress involves triage: something has to give. It’s spring in the chaparral. Blue dicks (native hyacinth) are rampant. Virgin’s bower (native clematis) is running riot, poppies and popcorn flower are popping up all over; and solanum and lupin bloom in blue profusion. Bush sunflowers are radiant.

It rained this year. The drought doomsters are perplexed at this entirely predictable turn of events. A cursory review of the rain fall records is all it takes to be assured that Southern California’s drought was fully within historical norms. Don’t be conflatin’ (with global warming that is).

Even in the chaparral, historical perspective is useful. Both the wisdom of reflection and the judgement of time are denied by the primacy of the moment where we become transfixed by the jet stream of trivia generated by the 24-hour media news-cycle - or blinkered by a few years of minimal rainfall. The slightly above average rainfall of 2016-2017 has everyone rejoicing – and me mourning the end of a five year holiday from weeds in the broken edges of the urban wildland. Natives are bred to drought, weeds from temperate Europe much less so.

In Washington, decision making happens in a place where its obsessions with a golden past deeply color its obsessions of the moment. There is a precedent. The Whig interpretation of history is a precursor to what some now call presentism: the predilection for focusing on what’s happening NOW. If all of history is tending towards its culmination in the present, then it is indeed the present that demands attention - the past serving as mere prelude. But the triumphalism of British mainstream historians in the age of Victoria who tended, as their great de-bunker Herbert Butterfield, wrote 1931, “to emphasize certain principles of progress in the past and to produce a story which is the ratification if not the glorification of the present” was surely the result of their satisfaction with the contemporaneous state of the world with Britain as its Imperial Master. They were blind to the impending decline of British hegemony - blind to threats of greater historical gravitas than those so ably batted away by the Foreign Secretaries of the day who relied on the rattle of the saber and the explosive shell, just as the Lord High Executioner and his Ministers rely on the brute force of the Tomahawk missile and drone delivered ordnance while seemingly unaware of more existential threats to their world.

In among the invasive grasses, those heralds of spring, peonies and goosefoot, still nestle. Deerweed, artemesia and sage show up as sage-scrub slowly re-establishes itself in the soils disturbed by residential development and before that of ranching and mixed farming. Soapweed sprouts in clusters, casually seeded by Chumash Indians who used its poison root to stun steelhead trout in Bear Creek. Native bunch grasses survive, but are crowded by introduced annual grasses. This morning, mist lay heavy in the valley, but rising above it, in the lee of the Santa Paula Ridge, the sun almost over the mountains, I spotted my first owl’s head clover of the season. Moments later, I saw fiddle neck still tightly curled but about to bloom.

In rhapsodizing over the emergence of vernal flora I am a consumer of the natural world situated, ideologically, somewhere in the mid-nineteenth century. Pursuing transcendence through transference, moving the ego aside and accessing what Jung calls the ‘voice of God’ (or at least, wallowing in an aesthetic reverie sufficient to submerge my quotidian concerns) I am following in the footsteps of Wordsworth, Emerson and Thoreau. Mine is a Romantic vision where I find profound aesthetic and spiritual value in the chaparral wilderness that surrounds me on the wildland edge of Ojai, California.

This reactionary excursion, from a position of little influence is, I hope, reasonably harmless. It is a step away from the present where we live in an age of ecology, our consciousness of the natural world informed by notions of complex and inter-related systems and shadowed by an understanding that civilization has impinged on these systems in profoundly irrevocable ways.

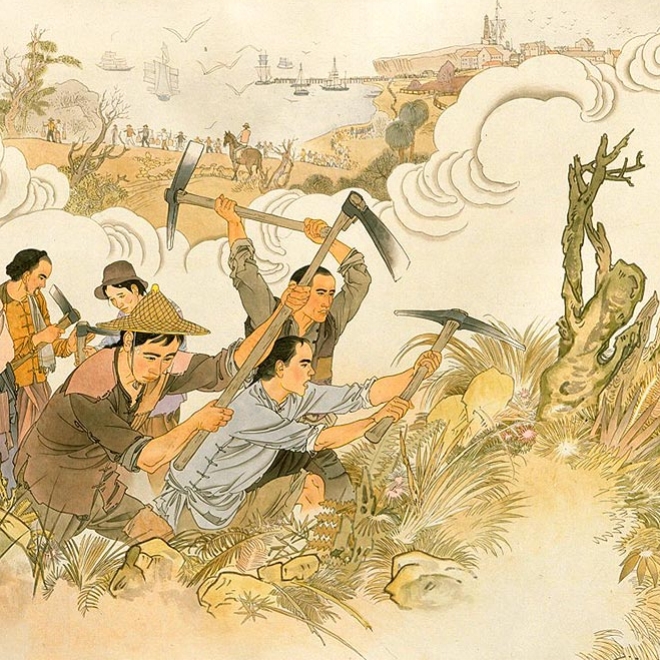

Our President meanwhile, from a position of some considerable influence, has retreated to a way of valuing the natural world prevalent at the very beginning of the European conquest of North America: when wilderness was worthless (unless to serve as terrain for the testing of one’s Christian faith); when wilderness was without intrinsic value until transformed by colonists and when its indigenous peoples had no rights to ownership precisely because of their failure to cultivate the land. By common law exegesis (or spiritual alchemy) land became property by virtue of its exploitation by Europeans.

As Jedediah Purdy outlines in his recent book, After Nature – A Politics for the Anthropocene, 2015, America was colonized by men and women resolute in their belief in this providential vision whereby the land existed only to serve human needs, its bounty a God-given gift to those who dared to make the land productive. In his pledge to Make America Great Again!, the President has embraced this vision which serves as divine justification for the mercenary exploitation of the environment. Within this pre-modern world view its protection would be tantamount to an attempt to turn the environment to Waste, a word, as Purdy notes, which in the providential vocabulary suggested wilderness - a place devoid of value.

Amy Davidson writes in a recent New Yorker, that in attempting to restrict the work of the EPA in controlling greenhouse gases, our President is guilty of “reckless endangerment”. The truth is this country is founded on exactly that ethos – ask any Native American even mildly cognizant of his people’s history.

It’s almost as if all of History is trending towards the seventeenth century. Despite his Twitterish presentism, the Baleful One has returned to the world of knee breeches, doublets and ruffs to find justification for an intensified extraction of the world’s resources. Yet there is a neo-liberal twist, a shard of the twenty first century inserted into his providential vision, for the environment will be fully monetized and the market will manage its inexorable decline.

Perhaps, as the earth trembles under the impact of its missiles, the earth’s air stultified by its toxic emissions, its rivers poisoned again by industrial waste and its over-fished seas swollen by its heedless carbon emissions, our land will, in the twenty-first century meaning of the words, be truly laid to waste……while its people (and their Representatives) remain comatose, (to continue our nature story) like so many stunned steelhead trout.